A Self-Guided Tour

by

William R. Kinloch

"Gentlemen, this is the place.”

George Seferis, Stratos the Mariner at the Dead Sea

George Seferis, Stratos the Mariner at the Dead Sea

Introduction

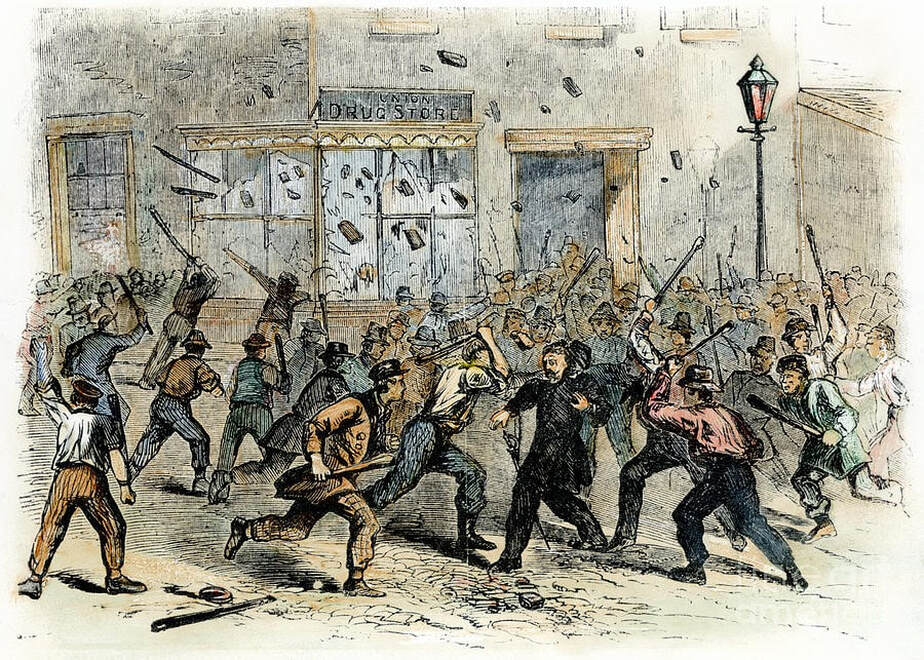

From July 13th to July 15th, 1863, New York City was racked by one of the most vicious race riots in the city’s history. The riot was not confined to just one part of the city. No part of the city was safe from the possibility of an attack by a mob. This guide is not comprehensive; many sites are omitted to keep the trip manageable. Only four sites are highlighted. These terrors not only really happened, they happened in specific locations. No plaques mark these places now. A man was lynched near a university building. The New York City store of the international clothier Zara is now at the site where once there was an orphanage with 233 black children and their teachers who fled for their lives when a fire was set by a mob determined to subject them to a horrific death. The place where the riot actually began is now a row of stores. A quiet residential street was the scene of brutal house-to-house fighting. Troops who had fought at the Battle of Gettysburg were rushed to New York and were camped in Gramercy Park, a private park.

To appreciate the reality of these events, the locations must be viewed like any of the more celebrated places in history. This history is ugly but important. Go to the place where Abraham Franklin was murdered. As George Seferis said, “This is the place.” Say a prayer, if you wish, for Franklin and all the rest who died in that riot. Like Franklin, they were real human beings, not abstract symbols, and this is where they died.

The War and the Draft

When the Civil War began with the firing upon Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, the Union Army was raised as an all-volunteer force. The Union war aim was the restoration of the Union. Lincoln admitted that he had no constitutional authority to abolish slavery. Enthusiastic young men formed regiments, some ethnic, such as the 69th New York ("The Fighting Irish.") Members of Volunteer Fire companies also enlisted (The New York Fire Zouaves)

To appreciate the reality of these events, the locations must be viewed like any of the more celebrated places in history. This history is ugly but important. Go to the place where Abraham Franklin was murdered. As George Seferis said, “This is the place.” Say a prayer, if you wish, for Franklin and all the rest who died in that riot. Like Franklin, they were real human beings, not abstract symbols, and this is where they died.

The War and the Draft

When the Civil War began with the firing upon Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, the Union Army was raised as an all-volunteer force. The Union war aim was the restoration of the Union. Lincoln admitted that he had no constitutional authority to abolish slavery. Enthusiastic young men formed regiments, some ethnic, such as the 69th New York ("The Fighting Irish.") Members of Volunteer Fire companies also enlisted (The New York Fire Zouaves)

|

By 1863, this initial enthusiasm for the war had died out. The war had not gone well, particularly in the East, where Robert E. Lee had defeated every Union general sent against him. The North had to conquer the South. If, by sheer endurance, the South prevented this, it could still gain its independence.

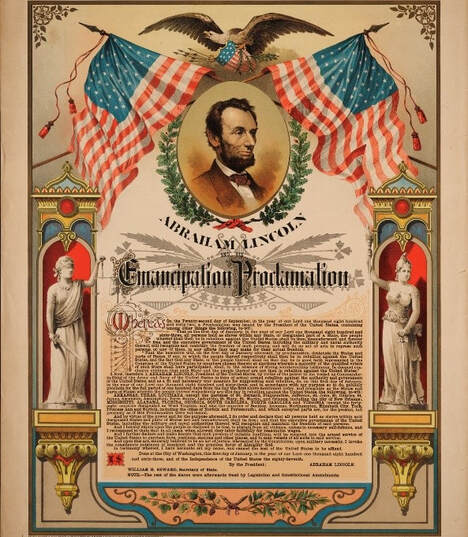

Lincoln had a two-part response to this ongoing crisis. First of all, he had broadened the scope of the war to include the abolition of slavery. On January 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect. |

Lincoln's second major initiative was the Federal draft, the first in U.S. history. The Confederacy had begun its own draft earlier, in April 1862. The Union draft was unpopular and unfair. A man whose name was called could get a year's deferment by paying $300. If a more permanent solution were needed, a substitute could be hired.

Being a soldier in the Civil War was highly dangerous. Battle casualties were enormous. The official losses for the Union Army for the 3-day battle at Gettysburg were 23,049. While battle concentrated the loses into a short span of time, in the long run, simply being in the army was even more likely to be fatal. Two hundred twenty thousand Union soldiers died of disease during the war.

Although the document had its limits, it changed the war. The Proclamation is usually regarded as a master political stroke by Lincoln, but there was a downside. Men who had enlisted to fight for the Union were not necessarily abolitionists. A Connecticut soldier wrote home: "When I enlisted I came to defend the flag and keep the Union as it was but they have turned this war into a niger(sic) war and I want to get out now as soon as posable(sic)." Desertion was a major problem for the Union's Army of the Potomac. By January 1863, the official number of desertions numbered 85,123.

Being a soldier in the Civil War was highly dangerous. Battle casualties were enormous. The official losses for the Union Army for the 3-day battle at Gettysburg were 23,049. While battle concentrated the loses into a short span of time, in the long run, simply being in the army was even more likely to be fatal. Two hundred twenty thousand Union soldiers died of disease during the war.

Although the document had its limits, it changed the war. The Proclamation is usually regarded as a master political stroke by Lincoln, but there was a downside. Men who had enlisted to fight for the Union were not necessarily abolitionists. A Connecticut soldier wrote home: "When I enlisted I came to defend the flag and keep the Union as it was but they have turned this war into a niger(sic) war and I want to get out now as soon as posable(sic)." Desertion was a major problem for the Union's Army of the Potomac. By January 1863, the official number of desertions numbered 85,123.

This was not solely a response to the Emancipation Proclamation. Army life was hard, and the Army of the Potomac's poor administration and history of defeats had brought morale to a very low pitch.

New York in 1863

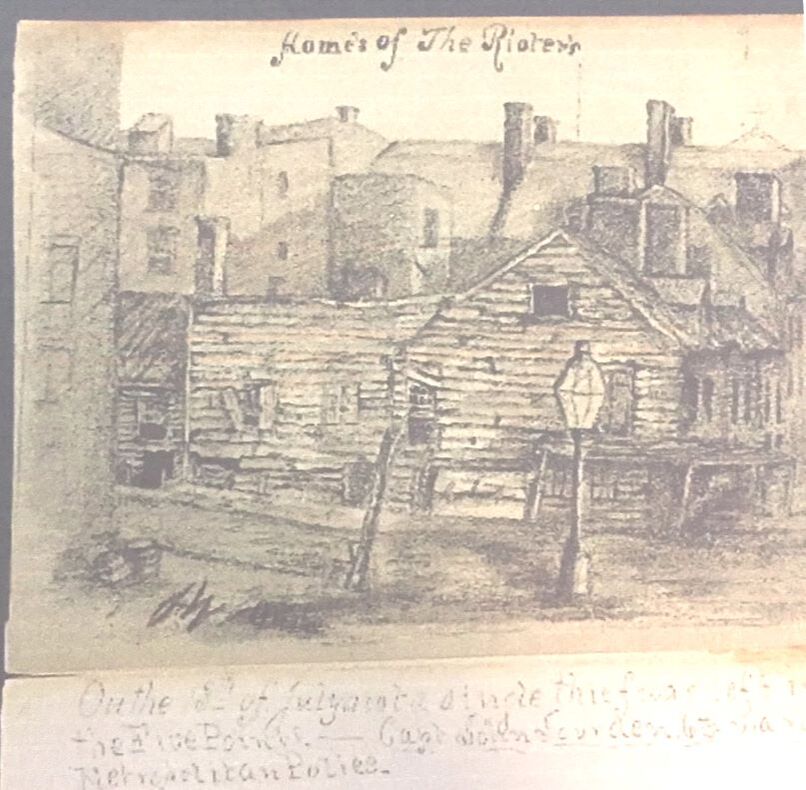

New York was a smaller city than it is now. Physically the rocky geography of Manhattan north of 50th Street made large scale development impractical. Bridges to Brooklyn and the other outer boroughs were not yet feasible. Skyscrapers would not be invented for several generations. A large part of Manhattan was industrial. Since the city could not grow, it had to compact. The people most affected by this compacting were those least able to pay for space and who also had to live near the source of their casual work.

|

The tenements were crowded. A report issued in 1856 found 75 people crowded into 12 very small, dirty rooms in the Five Points, New York's worst slum. Furniture was rare and battered. Above all, the city and its people were filthy. Baptism may have been the closest thing to taking a bath that many of the Irish ever got. They wore whatever rags they could get their hands on. Today's homeless would probably look better dressed than an Irishman of 1863—clothes get thrown away much sooner nowadays. |

The city itself was also 3rd world filthy. Cleaning contractors were politically appointed and often did no work for their pay. Slaughter houses were located in the city, and little effort was made to clean up their mess. Horses were still the major motive power for the city and an obvious source of pollution. When a new street cleaning machine was tried on Mulberry Street, the street filth was found to be three feet deep.

Water and sanitation were no better. The resulting disease was a major problem and one that could not be confined to the poor. The compacting of the city meant that the rich and poor lived quite closely together. The city must have been an epidemiologist's nightmare.

The police force, despite a large number of Irishmen in the ranks, was held in contempt by the Irish. The police were seen as the corrupt agents of the rich, arresting the poor for things the Irish did not consider crimes. In their native Ireland, the police had been agents of a foreign occupier. The informer was a stock villain, and resistance meant criminal actions. The police had only whatever respect that brute force could command; if they lost that edge they could expect no mercy from the crowd.

The police did not have a specially trained riot squad. The militia were the back-up for the police when public disorder got out of hand. During Lee's Gettysburg invasion, the New York militia regiments had been mobilized and sent down to Pennsylvania. That back-up had now been removed.

|

|

|

Green and Black

Blacks had been in New York since the days of New Amsterdam. Slavery was abolished in 1827, but abolition didn't bring equality or anything near it. Blacks were on the lowest rung of the ladder, social, economic, or any other ladder that anyone could think of. The abolitionists were more willing to give charity to blacks but social equality was explicitly denied by the Republicans in the 1860 campaign. In addition to the difficulties of being a poor and despised minority, the Blacks of New York had another problem. The Constitution had provided for the return of fugitive slaves and the Compromises of 1830 and 1850 had strenthened the Slaveowners' right to recover this property. The procedure for recovery hearings offered very little protection to the accused. In addition to the danger of these legal procedings, a kidnapping ring operated in New York from 1833 up to the Civil War. The kidnapping club's members included slave catchers, police officers, and judges. Daniel Ruggles, a Black Leader, helped to found The New York Committee of Vigilance. Ruggles and his organization played a cat and mouse game on the docks of New York. The slavers sought to smuggle people South to be sold, Ruggels sought to free them.

Courtesy of Ireland's Great Hunger Museum, Hamden, CT

Courtesy of Ireland's Great Hunger Museum, Hamden, CT

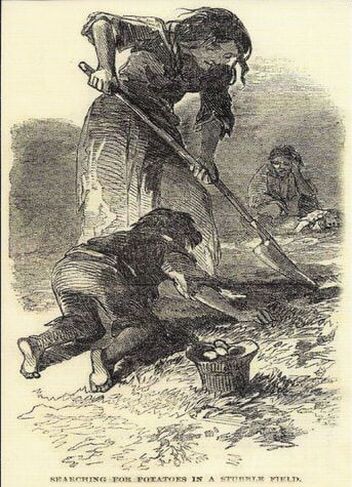

The Irish were newer to the city. Mass immigration from Ireland was spurred on by the An Ghorta Mor, the Great Potato Famine, 1845-1852. The Irish depended on potatoes to live and when the potatoes died, so did the Irish. A million died and 2 million fled, many to New York City.

I have not found any significant effort by any historian to connect the behavior of the Irish during the riots with their experience in the famine. A novel, Paradise Alley by Kevin Baker, touched upon the issue.

The famine was only 11 years earlier than the riot. The rioters were for the most part in their late teens to early 30s. Simple math, therefore, means they were about 5-20 years of age during the famine. Recent research by Dr. Janina Galler et al, published in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, March 12, 2013, suggests that malnutrition in infancy can have long lasting negative effects on personality. In his book on climate change, The Little Ice Age, Brian Fagan notes: "The lasting physical effects among the survivors included a high incident mental illness." Surely the effect of the famine on the rioters' behavior could provide a subject worthy of a Ph.D. thesis.

There is a question of whether the racist behavior of the mob was caused by the threat of black competition undercutting wages. There had been attacks on Blacks by Irish earlier. Blacks had been used as strike breakers in a longshoremen's strike earlier that year. The Democratic leadership was arguing that abolition would lead to the flood of cheap black labor to New York, destroying trade associations and customs, driving low wages to below starvation levels. In 1863, he who did not work did not eat and starvation would not have been an abstraction to the famine survivors.

The Tour

First Stop

The Destruction of the 9th District Draft Office

Monday, July 13

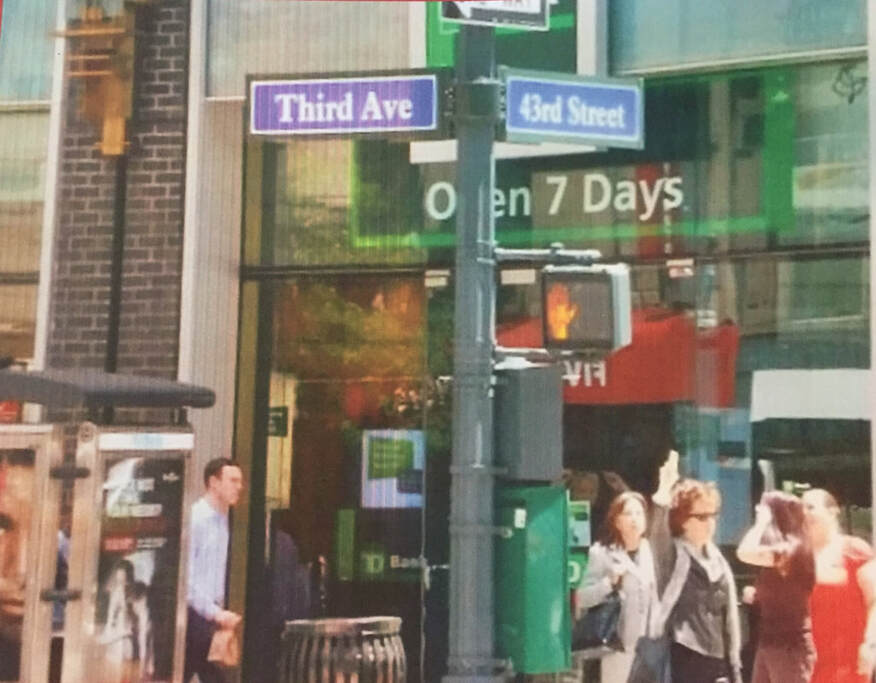

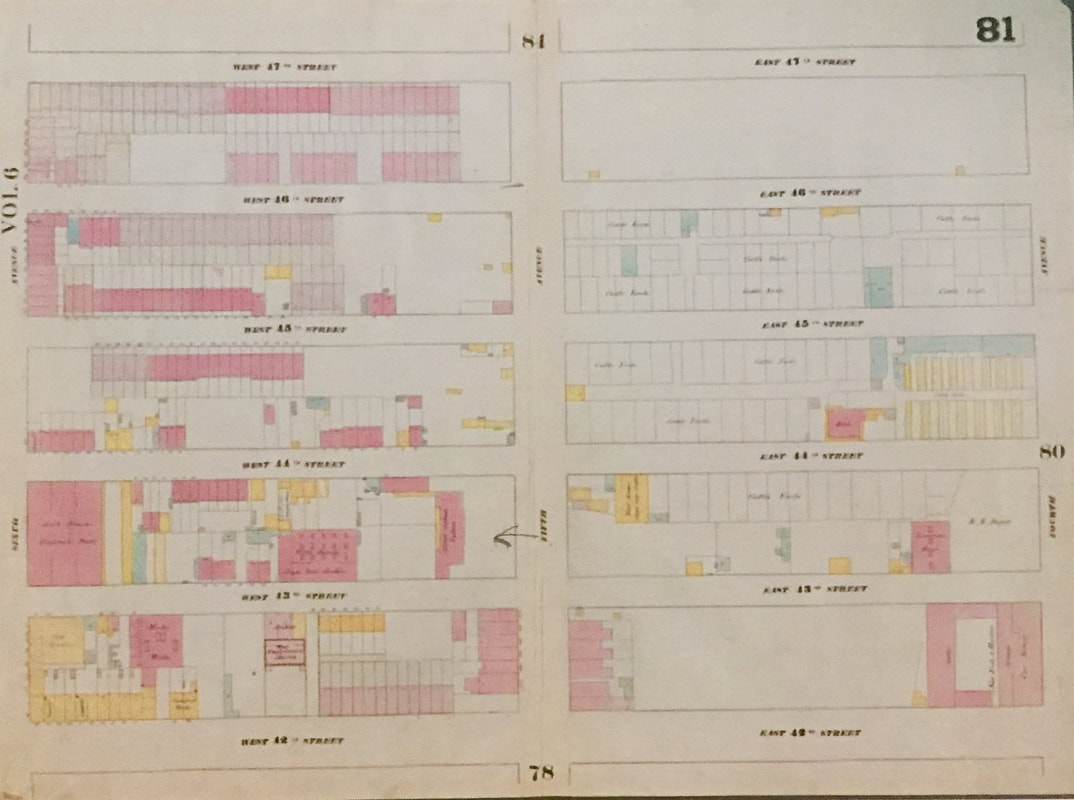

Our Tour begins where the Riot began, at the 9th District Draft Office (3rd & 43rd Streets. , 677 3rd Avenue.)

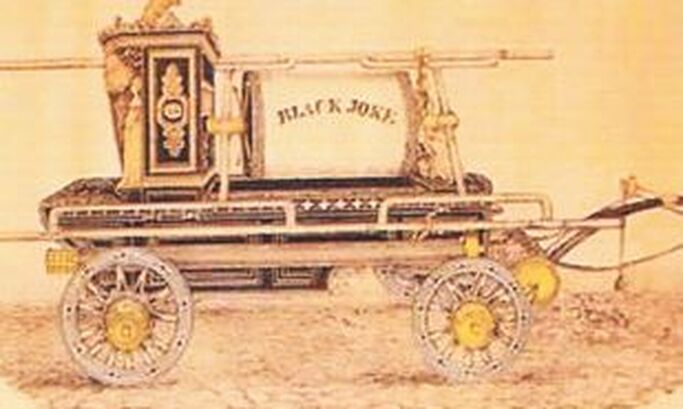

On Saturday, July 11th, the first drawing began. Heavy police presence was at hand. No problems occurred. However, the names of several members of the Black Joke Volunteer Fire Company, Number 33, were drawn, including the foreman's brother.

On Saturday, July 11th, the first drawing began. Heavy police presence was at hand. No problems occurred. However, the names of several members of the Black Joke Volunteer Fire Company, Number 33, were drawn, including the foreman's brother.

Civil War Draft Lottery Drum

Civil War Draft Lottery Drum

Volunteer Fire Companies were an odd institution in 1863 New York. Fire Companies were linked with gangs and political parties. Fire companies and gangs shared common members. Boss Tweed got his start in politics as a member of the Black Joke Fire Company. A fire often turned into a brawl as rival companies fought each other for the glory of putting out a fire. Rivalry was so intense that at one time the Black Joke Company not only fortified their firehouse but also had their own howitzer on premises to defend it.

Volunteer firemen had been exempted from the draft under the old militia system. This was not true under the new Federal draft, a fact which infuriated the firefighters. Thus, when the draft resumed on Monday, there existed an organized group of men with a tradition of violence, prepared to make their displeasure known. Because the first day had gone so smoothly, there were only 12 policemen at the draft office. Rumors of a large number of demonstrators reached the police and re-enforcements were sent for. Two massive columns of demonstrators made their way up 8th and 9th Avenues. They reached Central Park, which was still under construction, and then swung South to the 9th District Office. People waited for something to happen.

The riot began when "fire laddies" of the Black Joke came up in their engine, loaded with stones. They shattered the windows of the Draft Office and then set it on fire. The office was part of a four-building row, which, too, caught fire. Deputy Provost Edward S. Vanderpoel urged the Black Joke to put out these other fires. He was beaten for his trouble as was police officer John Cook who tried to help Vanderpoel. The police managed to save the draft records as they made a hasty retreat. The military was called in next.

A company of fit veteran troops might have ended the riot at this point, but no such force was available. The only military available was 70 men from the Invalid Corps, soldiers wounded or otherwise disabled. They were not fit for a combat assignment but they were the only military force available. Thirty-two of these soldiers were sent to confront the mob. The Invalids formed line but ran into increasing resistance. At 3rd Avenue and 43rd Street the mob charged. The Invalids got off one round before they were forced to flee. At least one of the soldiers was killed, one was never seen again, and a number were beaten. With the police and the army routed, the mob ruled New York.

The riot began when "fire laddies" of the Black Joke came up in their engine, loaded with stones. They shattered the windows of the Draft Office and then set it on fire. The office was part of a four-building row, which, too, caught fire. Deputy Provost Edward S. Vanderpoel urged the Black Joke to put out these other fires. He was beaten for his trouble as was police officer John Cook who tried to help Vanderpoel. The police managed to save the draft records as they made a hasty retreat. The military was called in next.

A company of fit veteran troops might have ended the riot at this point, but no such force was available. The only military available was 70 men from the Invalid Corps, soldiers wounded or otherwise disabled. They were not fit for a combat assignment but they were the only military force available. Thirty-two of these soldiers were sent to confront the mob. The Invalids formed line but ran into increasing resistance. At 3rd Avenue and 43rd Street the mob charged. The Invalids got off one round before they were forced to flee. At least one of the soldiers was killed, one was never seen again, and a number were beaten. With the police and the army routed, the mob ruled New York.

Second Stop

The Sack of the Colored Orphanage

Monday, July 13

The mob was not a single entity. No overall leadership existed. Rather, small ad hoc groups formed, attacked a piece of property or an individual, and then merged, dispersed, or reformed for some new destruction. Large numbers of the mob were drunk, and bars and liquor stores were a frequent target.

One of the bizarre customs of the riot was the insistence by members of the mob that the barkeep stand them a round of drinks. The rioters could have seized whatever they wanted. The proffer of a round of drinks was very likely less a gesture of sincere friendship than a desperate attempt to keep the rioters from destroying everything. Still, the form had to be observed. Perhaps the rioters were seeking to be recognized as a legitimate voice of the community.

One of the bizarre customs of the riot was the insistence by members of the mob that the barkeep stand them a round of drinks. The rioters could have seized whatever they wanted. The proffer of a round of drinks was very likely less a gesture of sincere friendship than a desperate attempt to keep the rioters from destroying everything. Still, the form had to be observed. Perhaps the rioters were seeking to be recognized as a legitimate voice of the community.

Black Children at the Orphanage in Better Days

Black Children at the Orphanage in Better Days

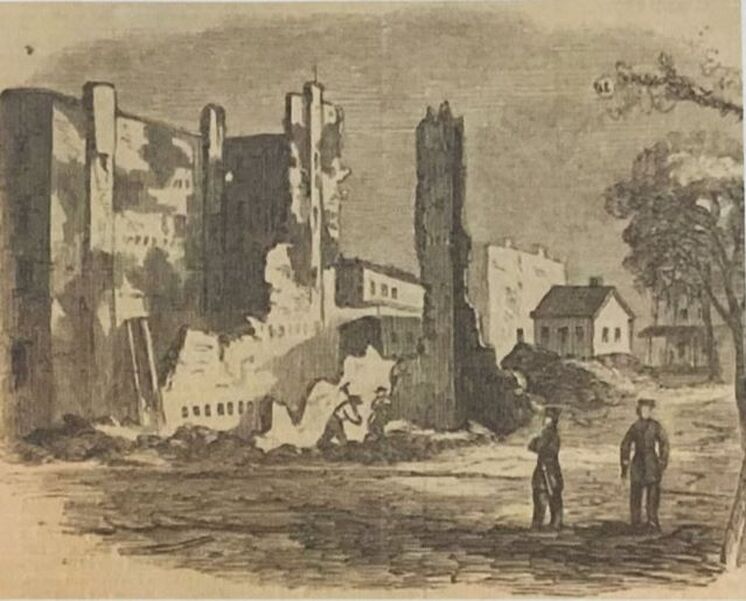

One obvious target was the Colored Orphanage at 5th Avenue between 42nd and 43rd Streets. The Orphanage had been founded by Quaker Anna Shotwell and had become quite famous over the last twenty years. A great deal of White charity went into the support of the orphanage.

One obvious target was the Colored Orphanage at 5th Avenue between 42nd and 43rd Streets. The Orphanage had been founded by Quaker Anna Shotwell and had become quite famous over the last twenty years. A great deal of White charity went into the support of the orphanage.

|

|

When the Orphanage opened, the orphans were only trained for the sort of menial work Blacks could attain. When Dr. James McCune Smith, the first Black licensed physician in New York, joined the Board of Directors, training became more ambitious. By 1863, the Orphanage was one of the most famous and most successful charitable institutions in the city. |

The mob that attacked the Orphanage may have been as few as two hundred, but they were determined. The mob set the Orphanage on fire. Some fire laddies tried to put out the blaze, but the mob cut their hoses. Shotwell realized she had to evacuate 233 terrified children in the face of an enraged mob.

She gathered the children and asked them if they trusted in God to bring them to safety. They said that they did and she began to evacuate over two hundred children as discretely as possible. For a moment it did not look as though she would succeed. As the mob threatened her and the children, one Irishman stepped forward and challenged the mob: "If there's a man among you, with a heart within him, come and help these children."

The mob turned on him, giving the children time to escape. Shotwell said the mob looked as though they were about to tear him to pieces. However, none of the known killed or wounded match the time and location of this incident. Therefore, he seems to have escaped without serious injury. The children fled to the protection of the 20th Precinct at 34th Street near 9th Avenue.

As anyone who has ever tried to herd a group of small children under even the most placid of circumstances will understand, moving 233 children that distance without some wandering off was impossible. One group of about twenty children became separated. They were surrounded by a mob yelling, "Murder the damned monkeys." They were rescued by a young Irishman named Paddy M'Caffrey, four stage drivers, and members of Engine Company 18. This ad hoc body guard got the children over to the 20th Precinct.

Two individual children also wandered off. A 6-year-old boy tried to gain shelter at a private residence but was refused by the lady of the house, fearing the wrath of the mob. She appealed to a passing Irishman. He happened to be a mason who worked for the Orphanage. He carried the boy home. The mason's daughter then carried him to one of the Black officers of the Orphanage. Another wanderer, a little girl, got lost crossing 7th Avenue, but was rescued by a Mr. Osborne and taken to his family's home.

With the orphans gone and with the Orphanage in flames, the sack of the Colored Orphanage began. The mob raced through the building, throwing furniture and clothing out of the window to the crowd below. People who run through a burning building to steal the furniture of an orphanage must be desperate for furniture.

The only child to die during the sack was killed at this time. Ten-year-old Jane Barry was struck and killed by a bureau thrown from a window of the Orphanage. She was probably an innocent bystander. I wonder what she was doing there. She must have been close to the building. A bureau is not going to travel that far from the point from where it was hurled. Did the excitement and spectacle of the event bring her in too close? It is also possible she was one of the poor, hoping for a few sticks of furniture, such as a bureau. The only certainty is that she died.

The sack of the Orphanage was the signal atrocity of the riot. Anger over the draft seems justifiable. Tension over jobs is at least understandable. Racism alone does not explain the mob's savagery. In 1863 almost every White person in America was a committed racist but few of these racists wanted to burn 233 children alive, or were willing to beat a defenseless child to death.

Behind the sack may have lurked envy. The mob's perception that the Black orphans were living better than many Irish children was quite accurate. This must have been intolerable to those who saw the orphans as "damned little monkeys," intolerable enough to spur them to do the unspeakable.

She gathered the children and asked them if they trusted in God to bring them to safety. They said that they did and she began to evacuate over two hundred children as discretely as possible. For a moment it did not look as though she would succeed. As the mob threatened her and the children, one Irishman stepped forward and challenged the mob: "If there's a man among you, with a heart within him, come and help these children."

The mob turned on him, giving the children time to escape. Shotwell said the mob looked as though they were about to tear him to pieces. However, none of the known killed or wounded match the time and location of this incident. Therefore, he seems to have escaped without serious injury. The children fled to the protection of the 20th Precinct at 34th Street near 9th Avenue.

As anyone who has ever tried to herd a group of small children under even the most placid of circumstances will understand, moving 233 children that distance without some wandering off was impossible. One group of about twenty children became separated. They were surrounded by a mob yelling, "Murder the damned monkeys." They were rescued by a young Irishman named Paddy M'Caffrey, four stage drivers, and members of Engine Company 18. This ad hoc body guard got the children over to the 20th Precinct.

Two individual children also wandered off. A 6-year-old boy tried to gain shelter at a private residence but was refused by the lady of the house, fearing the wrath of the mob. She appealed to a passing Irishman. He happened to be a mason who worked for the Orphanage. He carried the boy home. The mason's daughter then carried him to one of the Black officers of the Orphanage. Another wanderer, a little girl, got lost crossing 7th Avenue, but was rescued by a Mr. Osborne and taken to his family's home.

With the orphans gone and with the Orphanage in flames, the sack of the Colored Orphanage began. The mob raced through the building, throwing furniture and clothing out of the window to the crowd below. People who run through a burning building to steal the furniture of an orphanage must be desperate for furniture.

The only child to die during the sack was killed at this time. Ten-year-old Jane Barry was struck and killed by a bureau thrown from a window of the Orphanage. She was probably an innocent bystander. I wonder what she was doing there. She must have been close to the building. A bureau is not going to travel that far from the point from where it was hurled. Did the excitement and spectacle of the event bring her in too close? It is also possible she was one of the poor, hoping for a few sticks of furniture, such as a bureau. The only certainty is that she died.

The sack of the Orphanage was the signal atrocity of the riot. Anger over the draft seems justifiable. Tension over jobs is at least understandable. Racism alone does not explain the mob's savagery. In 1863 almost every White person in America was a committed racist but few of these racists wanted to burn 233 children alive, or were willing to beat a defenseless child to death.

Behind the sack may have lurked envy. The mob's perception that the Black orphans were living better than many Irish children was quite accurate. This must have been intolerable to those who saw the orphans as "damned little monkeys," intolerable enough to spur them to do the unspeakable.

Third Stop

The Lynching of Abraham Franklin

Tuesday, July 14

Black Coachman, Identity Unknown

Black Coachman, Identity Unknown

In 1863 there was no black district in New York. Blacks were scattered throughout the city. A block or two might be black, and these could be and often were defended. For the most part, the odds were one black man against a mob of white men, too many to fight.

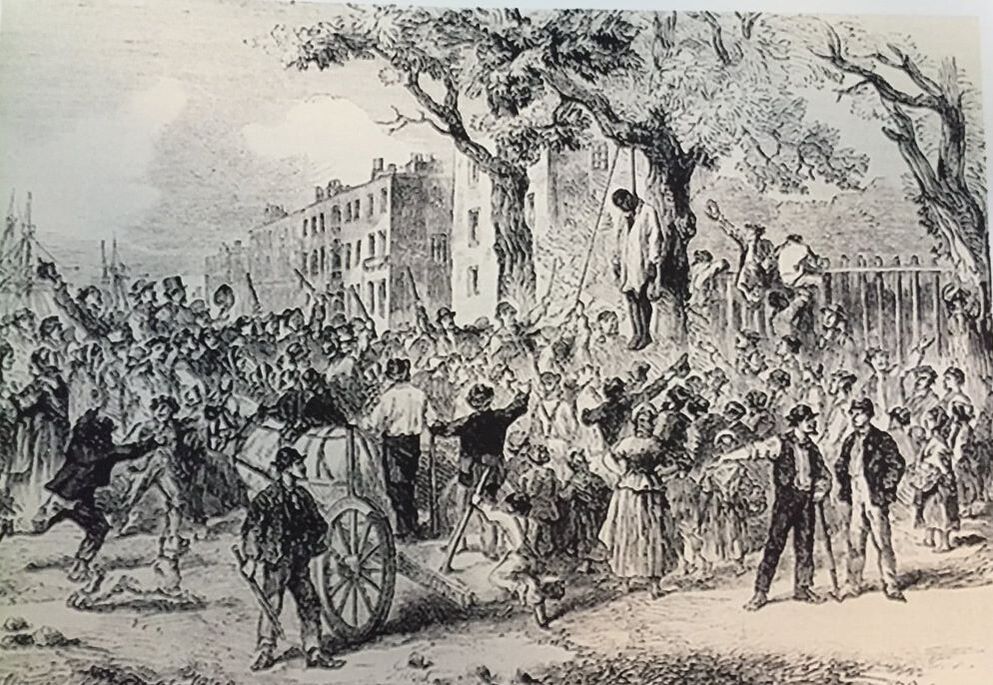

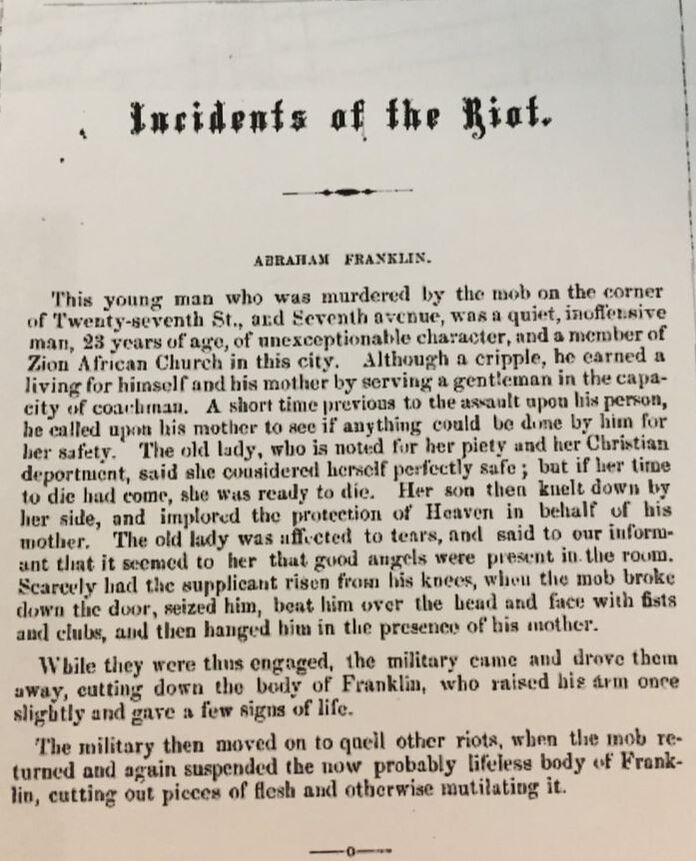

Five black men were lynched during the riot: James Costello, beaten and hanged on West 23rd Street on July 15th; Samuel Johnson, beaten and thrown into the East River on July 16th; William Jones, beaten and hanged on Clarkson Street on July 13th; William Williams, beaten to death on Leroy Street, July 14th; and Abraham Franklin, beaten and hanged on 7th Avenue & 28th Street.

In addition to the five lynching victims, many other people were beaten: police officers, soldiers, property owners who tried to save their property, blacks, and others who had somehow caught the attention of the mob. This number includes a Mohawk Indian and a white man returned from the tropics with too deep a tan. Why some people became beating victims and others lynching victims is unclear. Only in the case of James Costello can a clear reason be given. Costello had a pistol and wounded one of his pursuers, volunteer fireman William Mealy. The others, including Franklin, seemed to have died by chance.

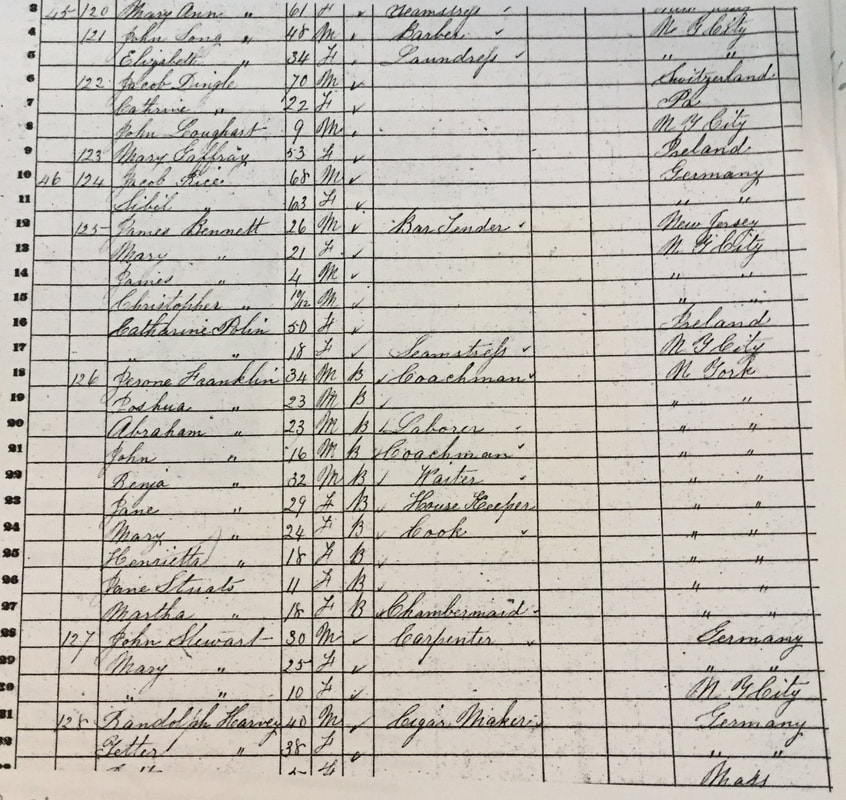

Franklin was a black coachman in his 20s, living on 7th Avenue & 29th Street. He was a cripple. In the 1860 census, Franklin's occupation is given as laborer. This must have been a difficult kind of work for him. He would have faced the double discrimination of being black and of being crippled in searching for work. The available work was like as not to be day labor jobs. When he could get work, his handicap might often make performing the job more difficult. His brother Jerome is listed as a coachman. This family connection may have paved the way for Franklin's new occupation in 1863.

There are two slightly different versions of Franklin's murder. In one version he lived with his sister. A mob broke into their home, beat up his sister, then dragged Franklin outside and lynched him.

Five black men were lynched during the riot: James Costello, beaten and hanged on West 23rd Street on July 15th; Samuel Johnson, beaten and thrown into the East River on July 16th; William Jones, beaten and hanged on Clarkson Street on July 13th; William Williams, beaten to death on Leroy Street, July 14th; and Abraham Franklin, beaten and hanged on 7th Avenue & 28th Street.

In addition to the five lynching victims, many other people were beaten: police officers, soldiers, property owners who tried to save their property, blacks, and others who had somehow caught the attention of the mob. This number includes a Mohawk Indian and a white man returned from the tropics with too deep a tan. Why some people became beating victims and others lynching victims is unclear. Only in the case of James Costello can a clear reason be given. Costello had a pistol and wounded one of his pursuers, volunteer fireman William Mealy. The others, including Franklin, seemed to have died by chance.

Franklin was a black coachman in his 20s, living on 7th Avenue & 29th Street. He was a cripple. In the 1860 census, Franklin's occupation is given as laborer. This must have been a difficult kind of work for him. He would have faced the double discrimination of being black and of being crippled in searching for work. The available work was like as not to be day labor jobs. When he could get work, his handicap might often make performing the job more difficult. His brother Jerome is listed as a coachman. This family connection may have paved the way for Franklin's new occupation in 1863.

There are two slightly different versions of Franklin's murder. In one version he lived with his sister. A mob broke into their home, beat up his sister, then dragged Franklin outside and lynched him.

Franklin's mother gave a different version of her son's murder, in a statement to the Merchants' Relief Committee. She told the interviewer for the Committee that Franklin had stopped by her home on 7th Avenue and 28th Street to check up on her. The mob spotted him and broke into her apartment. Franklin was dragged out into the street.

While his mother watched helplessly, Franklin was kicked and beaten by a mob led by Irish laborer George Glass. He shouted for a rope. Mark Silva, a Jewish immigrant from England, provided one. Franklin was hanged from a lamp post.

Then soldiers from the 35th Street Armory came and dispersed the mob. Franklin, still alive, was cut down and left in the street. The soldiers left and the mob returned. Franklin was hanged again.

When he did die, the mob had a carnival. Pieces of his flesh were cut off. A 16 year old butcher's boy, Patrick Butler, took Franklin's body by the genitalia and dragged it about the street. Franklin's body was never identified.

Fourth Stop

The Battle of 22nd Street

Thursday, July 16

The rule of the mob was increasingly contested. By Wednesday, July 15th, small groups of well-armed soldiers, very willing to use deadly force, won most of their fights against the rioters. Non-rioters organized and began to fight back, too. Their numbers, however, were not large enough to prevent new outbreaks of violence.

Reinforcements began to arrive late Wednesday. First came the 74th New York National Guard at 10:00pm, followed by the 65th and the 152nd New York, and the 26th Michigan Regiments. At 4:30 am on Thursday, the 7th New York Regiment returned from Pennsylvania, landed on Canal Street, marched past Governor Seymour's headquarters at the St. Nicholas Hotel and down Broadway. There were now over 4,500 troops available to the authorities.

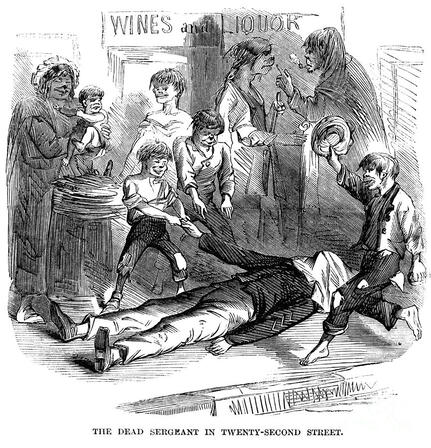

The rioters were on the defensive, falling back into fortified enclaves. The crises came when 80 dismounted cavalry, under Colonel Thaddeus Mott stationed at Gramercy Park tried to move up 22nd Street at about 4:00pm. They ran into heavy sniper fire from the houses on both sides of the street. They fell back, leaving the body of Sergeant Charles Davis behind.

Colonel Mott went to report his repulse to his commander, General Harvey Brown. Brown was furious at Mott for leaving his command and ordered him to return to his men. "What are you doing here, Sir? Go, Sir. Your place is with your men." Brown and Police Commissioner Acton sent reinforcements, a mixed force of police and 160 Federal troops under Captain Putnam, who had already shown an aptitude the day before for street fighting.

The street was quiet when Putnam arrived. The body of Sgt. Davis was in the street. Putnam commandeered a carriage from a livery stable. The driver tried to refuse, being afraid of the mob. Putnam promised to protect him if he agreed and to shoot him if he did not. The driver saw the wisdom of compliance and Davis' body was put into the carriage. At that moment, firing broke out from the roofs and windows of 22nd Street. Putnam sent out skirmishers and began house-to -house fighting. Room by room, house by house, 22nd Street was cleared. Desperate rioters were cornered and if they offered any resistance, they were killed. If, " Take no prisoners," was not the order given (as it had been at other times during the riot), clearly, "Shoot to Kill," was the rule. The rioter who wanted to surrender had better not delay.

The soldiers and police fought their way up 22nd Street, and then turned North on 3rd Avenue. At 31st Street, the rioters' resistance again began to stiffen. Houses had been fortified and again house-to-house fighting was required. Artillery fired antipersonnel rounds to clear 3 rd Avenue. The mob was finally broken.

The battle of 22nd Street did not end all fighting instantly, but it was the last pitched battle of the riot. After this, it was a matter of mopping up operations.

Reinforcements began to arrive late Wednesday. First came the 74th New York National Guard at 10:00pm, followed by the 65th and the 152nd New York, and the 26th Michigan Regiments. At 4:30 am on Thursday, the 7th New York Regiment returned from Pennsylvania, landed on Canal Street, marched past Governor Seymour's headquarters at the St. Nicholas Hotel and down Broadway. There were now over 4,500 troops available to the authorities.

The rioters were on the defensive, falling back into fortified enclaves. The crises came when 80 dismounted cavalry, under Colonel Thaddeus Mott stationed at Gramercy Park tried to move up 22nd Street at about 4:00pm. They ran into heavy sniper fire from the houses on both sides of the street. They fell back, leaving the body of Sergeant Charles Davis behind.

Colonel Mott went to report his repulse to his commander, General Harvey Brown. Brown was furious at Mott for leaving his command and ordered him to return to his men. "What are you doing here, Sir? Go, Sir. Your place is with your men." Brown and Police Commissioner Acton sent reinforcements, a mixed force of police and 160 Federal troops under Captain Putnam, who had already shown an aptitude the day before for street fighting.

The street was quiet when Putnam arrived. The body of Sgt. Davis was in the street. Putnam commandeered a carriage from a livery stable. The driver tried to refuse, being afraid of the mob. Putnam promised to protect him if he agreed and to shoot him if he did not. The driver saw the wisdom of compliance and Davis' body was put into the carriage. At that moment, firing broke out from the roofs and windows of 22nd Street. Putnam sent out skirmishers and began house-to -house fighting. Room by room, house by house, 22nd Street was cleared. Desperate rioters were cornered and if they offered any resistance, they were killed. If, " Take no prisoners," was not the order given (as it had been at other times during the riot), clearly, "Shoot to Kill," was the rule. The rioter who wanted to surrender had better not delay.

The soldiers and police fought their way up 22nd Street, and then turned North on 3rd Avenue. At 31st Street, the rioters' resistance again began to stiffen. Houses had been fortified and again house-to-house fighting was required. Artillery fired antipersonnel rounds to clear 3 rd Avenue. The mob was finally broken.

The battle of 22nd Street did not end all fighting instantly, but it was the last pitched battle of the riot. After this, it was a matter of mopping up operations.

Aftermath

A number of riots occurred in other cities to protest the draft, none as serious as New York's riot. With the crushing of the New York riot, no question remained that the draft would be enforced. Actually, far fewer men were drafted than volunteered. These volunteers were a suspect lot including a large number of professional "bounty jumpers," men who enlisted, took the enlistment bounty, deserted, and reenlisted in another regiment for a another bounty. They were despised by the army. Officers began to prefer draftees to volunteers.

With so much crime having been committed during the riots, legal proceedings had to follow. No one was convicted of any of the murders, including the three men known to have been involved in Franklin's lynching. The grand jury refused to indict Glass. Silva was indicted of 1 st degree murder but was never brought to trial. Butler denied involvement with the murder but admitted to desecrating Franklin's corpse. This posed a problem for the authorities, there being no specific law forbidding the dragging of a corpse by its genitals. They settled on an act of public indecency, and Butler was sent to the equivalent of Juvenile Detention.

The stiffest sentences, 15 years at hard labor, were given to a pair of men from Philadelphia, John Conway and Michael Doyle. They stole a $3.00 hat. Four of those killed in the riot are buried at Green-Wood Cemetery, 500 25th Street, Brooklyn, NY 11232. William Elder is listed as, "Killed in a Riot" by Green-Wood. Thomas Gibson, age 24, a native of Ireland was shot on July 14th at 2 nd Avenue and 21 st Street and died at Bellevue Hospital. Charles Fisbeck, ten years old, was shot and killed on July 14th . Five-year-old Elizabeth Marshall was shot and killed on July 15th.

Coda

One final question should be asked: was participation in the riot fun? Obviously, there are more profound causes. There is the long history of American racism, the long history of anti-Catholicism, the competition for work, the unwillingness of young men to join the army of their own will, the limited life prospects of the members of the mob, and the utter unfairness of the draft law. A strong sexual element also existed.

This was not a new phenomenon, nor one confined to lower class Irishmen, nor did it end with the riots. Patricia Cline Cohen, in her book, The Murder of Helen Jewett demonstrates a number of attacks on brothels with white prostitutes and black customers. Not until Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) was marriage across racial lines recognized as a constitutional right. The line between protecting our women and controlling our women, if it exists at all, is a very fine one.

In his book on the riots, Ivor Bernstein argues that the period in which the riots occurred was one of high anxiety for a young Irishman thinking about his future. To become an adult man, he would need to be able to support a wife and child. New York was a place with few certainties. Just to carry on as your father had done was not possible. Added to this, many of these young men had witnessed, or at least heard of their father’s abject failure to fulfill the most basic duty of the head of a family—to keep his family from starvation.

Apply these factors to 16-year-old Patrick Butler, who desecrated Franklin’s corpse. During the riot, he was part of a happy group of men. Adrian Cooke describes the mob as euphoric. Butler was intensely living in the present. He had no time to worry about future responsibilities. He was under no confining supervision—not his parents, not his boss, not his priest, not the police, not the army. While he was not directly involved in the murder, he was a part of the crowd who had won such a signal victory over a hated enemy. He then became the center of everyone’s attention and approval, dragging the body up and down the street. Patrick Butler was having the time of his life.

Social order is maintained by the billyclubs of the police. If these are not enough, the guns of the army are next. Until order is restored, chaos reigns. When the collective id of a crowd is released, a terrible freedom is born.

With so much crime having been committed during the riots, legal proceedings had to follow. No one was convicted of any of the murders, including the three men known to have been involved in Franklin's lynching. The grand jury refused to indict Glass. Silva was indicted of 1 st degree murder but was never brought to trial. Butler denied involvement with the murder but admitted to desecrating Franklin's corpse. This posed a problem for the authorities, there being no specific law forbidding the dragging of a corpse by its genitals. They settled on an act of public indecency, and Butler was sent to the equivalent of Juvenile Detention.

The stiffest sentences, 15 years at hard labor, were given to a pair of men from Philadelphia, John Conway and Michael Doyle. They stole a $3.00 hat. Four of those killed in the riot are buried at Green-Wood Cemetery, 500 25th Street, Brooklyn, NY 11232. William Elder is listed as, "Killed in a Riot" by Green-Wood. Thomas Gibson, age 24, a native of Ireland was shot on July 14th at 2 nd Avenue and 21 st Street and died at Bellevue Hospital. Charles Fisbeck, ten years old, was shot and killed on July 14th . Five-year-old Elizabeth Marshall was shot and killed on July 15th.

Coda

One final question should be asked: was participation in the riot fun? Obviously, there are more profound causes. There is the long history of American racism, the long history of anti-Catholicism, the competition for work, the unwillingness of young men to join the army of their own will, the limited life prospects of the members of the mob, and the utter unfairness of the draft law. A strong sexual element also existed.

This was not a new phenomenon, nor one confined to lower class Irishmen, nor did it end with the riots. Patricia Cline Cohen, in her book, The Murder of Helen Jewett demonstrates a number of attacks on brothels with white prostitutes and black customers. Not until Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) was marriage across racial lines recognized as a constitutional right. The line between protecting our women and controlling our women, if it exists at all, is a very fine one.

In his book on the riots, Ivor Bernstein argues that the period in which the riots occurred was one of high anxiety for a young Irishman thinking about his future. To become an adult man, he would need to be able to support a wife and child. New York was a place with few certainties. Just to carry on as your father had done was not possible. Added to this, many of these young men had witnessed, or at least heard of their father’s abject failure to fulfill the most basic duty of the head of a family—to keep his family from starvation.

Apply these factors to 16-year-old Patrick Butler, who desecrated Franklin’s corpse. During the riot, he was part of a happy group of men. Adrian Cooke describes the mob as euphoric. Butler was intensely living in the present. He had no time to worry about future responsibilities. He was under no confining supervision—not his parents, not his boss, not his priest, not the police, not the army. While he was not directly involved in the murder, he was a part of the crowd who had won such a signal victory over a hated enemy. He then became the center of everyone’s attention and approval, dragging the body up and down the street. Patrick Butler was having the time of his life.

Social order is maintained by the billyclubs of the police. If these are not enough, the guns of the army are next. Until order is restored, chaos reigns. When the collective id of a crowd is released, a terrible freedom is born.

Bibliography

This not being a scholarly piece, there are no footnotes and only a general bibliography.

Two reasonably available books are the principle sources for the facts quoted herein. The Armies of the Street, Adrian Cook (University Press of Kentucky 1974) has very useful appendixes listing by name the killed, wounded, and arrested including disposition of their cases. The Devil's Own Work, Barnet Schecter (Walker Publishing 2005) has a good appendix listing sites of interest. Another source, The New York City Draft Riots, by Ivor Bernstein (Oxford University Press, 1990) is more concerned with the post-riot political settlement than the details of the riot itself.

The Civil War and New York, Ernest A. McKay ( University of Syracuse, 1990) gives an overview of the city during the war. Copperheads, Jennifer L. Welder (Oxford University Press, 2006) covers the Northern political opposition to Lincoln. For an account of David Ruggles and his struggle against the Kidnapping Club see The Kidnapping Club by Johnathon Daniel Wells (Bold Type Books 2020) For the effect of the draft on the military, The Army of the Potomac Trilogy , Bruce Catton (Doubleday, 1951-53) was used. For the Irish Famine, The Great Hunger, by Cecil Woodham-Smith (Signet Books, 1964), was used.

Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery_ , Jeffrey Richmond (Green-Wood Cemetery, 1998) gives the burials. The report of the merchants' committee which investigated the riot, stating that Franklin had gone to check on his mother, seems to be based on an interview with Franklin’s mother and therefore, probably is the correct version. Paradise Alley, a novel by Kevin Baker touched on the post-traumatic damage of the An Gorta Mor.

This not being a scholarly piece, there are no footnotes and only a general bibliography.

Two reasonably available books are the principle sources for the facts quoted herein. The Armies of the Street, Adrian Cook (University Press of Kentucky 1974) has very useful appendixes listing by name the killed, wounded, and arrested including disposition of their cases. The Devil's Own Work, Barnet Schecter (Walker Publishing 2005) has a good appendix listing sites of interest. Another source, The New York City Draft Riots, by Ivor Bernstein (Oxford University Press, 1990) is more concerned with the post-riot political settlement than the details of the riot itself.

The Civil War and New York, Ernest A. McKay ( University of Syracuse, 1990) gives an overview of the city during the war. Copperheads, Jennifer L. Welder (Oxford University Press, 2006) covers the Northern political opposition to Lincoln. For an account of David Ruggles and his struggle against the Kidnapping Club see The Kidnapping Club by Johnathon Daniel Wells (Bold Type Books 2020) For the effect of the draft on the military, The Army of the Potomac Trilogy , Bruce Catton (Doubleday, 1951-53) was used. For the Irish Famine, The Great Hunger, by Cecil Woodham-Smith (Signet Books, 1964), was used.

Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery_ , Jeffrey Richmond (Green-Wood Cemetery, 1998) gives the burials. The report of the merchants' committee which investigated the riot, stating that Franklin had gone to check on his mother, seems to be based on an interview with Franklin’s mother and therefore, probably is the correct version. Paradise Alley, a novel by Kevin Baker touched on the post-traumatic damage of the An Gorta Mor.